Working to End Violence Against Women

COVID-19 and Family Violence

Our Violence Against Women Framework states:

Violence against women and their children is a prevalent, serious and preventable human rights abuse. One woman a week is murdered by a current or former partner and thousands more are injured or made to live in fear. The social, health and economic costs of violence against women are enormous. Preventing such violence is a matter of national urgency, and can only be achieved if we all work together.

The Centre for Non-Violence was established in 1990, initially to respond to the lack of safe and secure accommodation options for homeless young women. The progression to obtaining funding to establish the regional domestic and family violence outreach service was logical, given that the majority of young women who were at risk of or experiencing homelessness were at risk of, or had experienced family violence.

Whilst there are many types of gender based violence that women experience such as sexual assault, early/forced marriage, female genital mutilation, trafficking etc, the funded work of CNV relates to violence perpetrated towards a woman (and her children) by a current or ex-partner or family member.

Broadly CNV understands that gender based violence is both a cause and consequence of gender and other social inequalities.

Whilst most of our funded work relates to what is defined as “family/domestic/intimate partner violence”, we also understand that we must work towards genuine social change to end not only this violence, but all forms of violence against women.

It is important we continue to challenge misinformation about the drivers of violence, during this time.

We will see many excuses made for men’s violence towards women and children in coming months, which can only cause further harm.

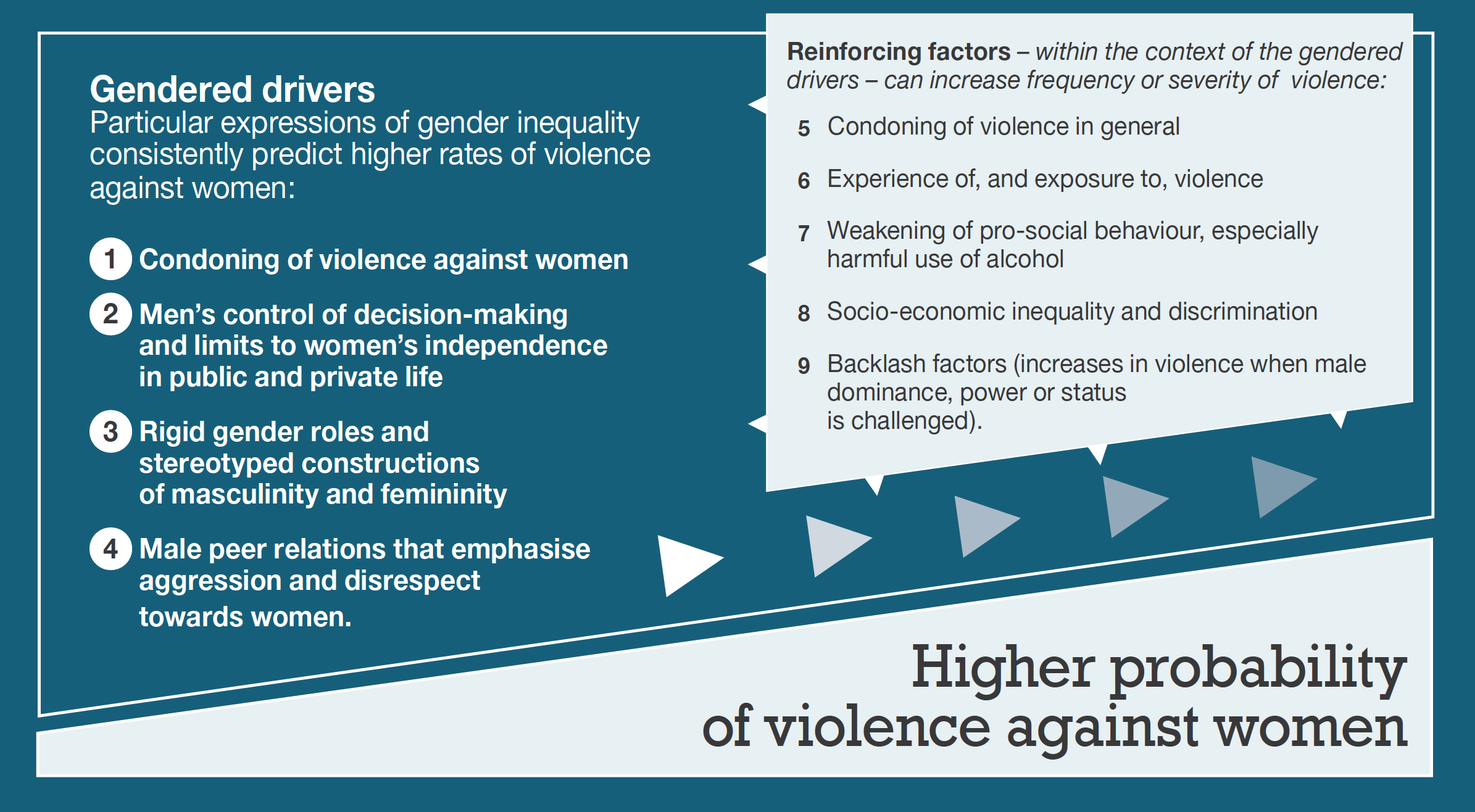

We must continue to remind the community that the main driver of violence against women is gender inequality – which includes attitudes that excuse or condone violence, limit women’s decision-making, adhere to rigid gender roles and disrespect women.

We must continue to hold perpetrators to account and place the onus on them to change their attitudes and behaviour.

The Change the Story framework developed by OurWatch, ANROWS and VicHealth states:

Gender inequality is a social condition characterised by unequal value afforded to men and women and an unequal distribution of power, resources and opportunity between them. It results from, or has historical roots in, laws or policies formally constraining the rights and opportunities of women. Gender inequality is maintained and perpetuated today through structures that continue to organise and reinforce an unequal distribution of economic, social and political power and resources between women and men; limiting social norms that prescribe the type of conduct, roles, interests and contributions expected from women and men; and the practices, behaviours and choices made on a daily basis that reinforce these gendered structures and norms.

Gender inequality is influenced by other forms of systemic social, political and economic disadvantage and discrimination. Other factors interact with or reinforce gender inequality to contribute to increased frequency and severity of violence against women, but do not drive violence in and of themselves.

The Overall Context

Violence against women is disturbingly common in Australia

One in three Australian women has experienced physical violence, and almost one in five has experienced sexual violence. One in four Australian women has experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a current or former male partner. However, the true scale of the problem is likely much greater: only a small proportion of women ever reports violence, and many instances of violence go unreported.

Violence is varied, insidious and disempowers women

Violence against women is not only physical: it can include sexual, economic, psychological, verbal or emotional abuse, as well as neglect, property damage, harassment, stalking, or coercive control. All types of violence against women are insidious because they lead to ongoing fear and trauma, and loss of freedom and choice. Violence against women and their children frequently occurs in familiar everyday environments, such as the home, in the workplace, at school and in the local community, with mobile technologies now making it possible for perpetrators to encroach on every aspect of a victim’s life.

Children are also victims of violence against women

Around three in four women who cared for children during a previous violent relationship report that those children saw or heard violence. Children who witness violence experience similar trauma and negative outcomes as children who are physically abused. However, children are not always treated as victims in their own right.

Violence affects women from all walks of life

Violence against women is pervasive – it crosses geographic, economic and social boundaries. Young women, women with a lower socioeconomic position, women with disabilities or long-term health conditions, and women living in regional, rural and remote areas are more likely to experience partner violence. Women who are employed and women with post-school qualifications are also at risk.

Some women are at greater risk of violence or face greater barriers in seeking help

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 34 times more likely to be hospitalised from partner assaults than the general female population. Women with disabilities are also more likely to experience violence than women without a disability. Women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may face violence as well as other challenges, such as language barriers and social isolation. Women who live in regional, rural or remote areas are often a long way from services and face barriers to escaping violence and seeking support. Women who experience other types of disadvantage and stigma are also at higher risk of violence or can experience difficulties accessing support.

Too often we justify and minimize violence against women

Very few Australians would explicitly condone violence against women. However, it is shamefully common for Australians to justify or minimise it. As a society, we excuse violence against women whenever we seek to justify the actions of perpetrators. Advice such as ‘don’t wear short skirts,’ ‘don’t drink alcohol’ and ‘don’t provoke men’ all implicitly assign responsibility for safety to the victim and justify or minimise the perpetrator’s behaviour. These attitudes begin at a very young age. Australians as young as five years old typically minimise boys’ behaviour and blame girls for bringing violence upon themselves. Underlying these harmful attitudes is a fundamental lack of gender equality in Australia.

A new mindset is needed

It is time to stop placing the burden on women and minimising the behaviour of men who perpetrate violence. A new approach is required that begins by recognising that victims will not be safe if the behaviour and attitudes of perpetrators are not addressed. It should empower women and their children and challenge pervasive community attitudes that reinforce gender inequality. Every woman has the right to feel safe, and so do her children.

The Facts

- Since the age of 15:

• 1 in 5 Australian women had experienced sexual violence

• 1 in 3 Australian women had experienced physical violence

• 1 in 4 Australian women had experienced physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner. - Victoria Police attended approximately 70,000 incidents of family violence in 2014/2015.

- At least one woman a week is killed by a current or former partner.

- Intimate partner violence is the leading contributor to death, illness and disability in Australian women aged 15 to 44 years than any other preventable risk factor.

- Domestic or family violence is the leading cause of homelessness in Australia.

- Violence is experienced differently by different women. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience both far higher rates and more severe forms of violence compared to other women.

- Young women (18 to 24 years) experience significantly higher rates of physical and sexual violence than women in older age groups.

- There is growing evidence that women with disabilities are also more likely to experience violence.

- While all violence is unacceptable, regardless of the sex of the victim or perpetrator, there are distinct differences in the ways in which men and women perpetrate and experience violence. The vast majority of violent acts – whether against men or women – are perpetrated by men.

- Men are more likely to experience violence by other men in public places, while women are more likely to experience violence from men they know, often in the home.

- Women are five times more likely than men to require medical attention or hospitalisation as a result of intimate partner violence, and five times more likely to report fearing for their lives.

- The combined social, economic and health costs of violence against women and their children drain the Australian economy of $13.6 billion a year, and this cost is rising.

The experience of CNV is consistent with the broader population level data. We are seeing increased reporting to police, and overall greater demand for services and support across our region. We see a direct correlation between increased awareness of violence against women, primarily family and domestic violence and increased request for support.

What is violence?

1. Violence Against Women

Broadly, ‘violence against women’ includes a range of behaviours and actions that aim to control a woman through fear. These may include physical, sexual, emotional and psychological abuse and assault, the threat of violence, coercion, emotional manipulation, financial abuse and forced marriage.

2. Victorian Government definition of Family Violence

Under the Victorian Government's Family Violence Protection Act 2008 Family violence is defined as:

(a) behaviour by a person towards a family member of that person if that behaviour

- is physically or sexually abusive; or

- is emotionally or psychologically abusive; or

- is economically abusive; or

- is threatening; or

- is coercive; or

- in any other way controls or dominates the family member and causes that family member to feel fear for the safety or wellbeing of that family member or another person;

or

(b) behaviour by a person that causes a child to hear or witness, or otherwise be exposed to the effects of, behaviour referred to in paragraph (a).

3. Family Violence definition

– Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander communities

Family violence is used in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context to describe the range of physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses perpetrated within families and communities. It also includes lateral violence, which describes how historical and ongoing trauma and social and cultural oppression move through kinship networks, communities and generations.

Addressing violence in this case must take a much wider view than just focusing on the victim-perpetrator relationship. It must also consider the way a number of individuals may work together to harm an individual, family, or another group (for example, through gossiping, undermining, jealousy, bullying, shaming, social exclusion, family feuding, organisational conflict, social pressures and other social dynamics).

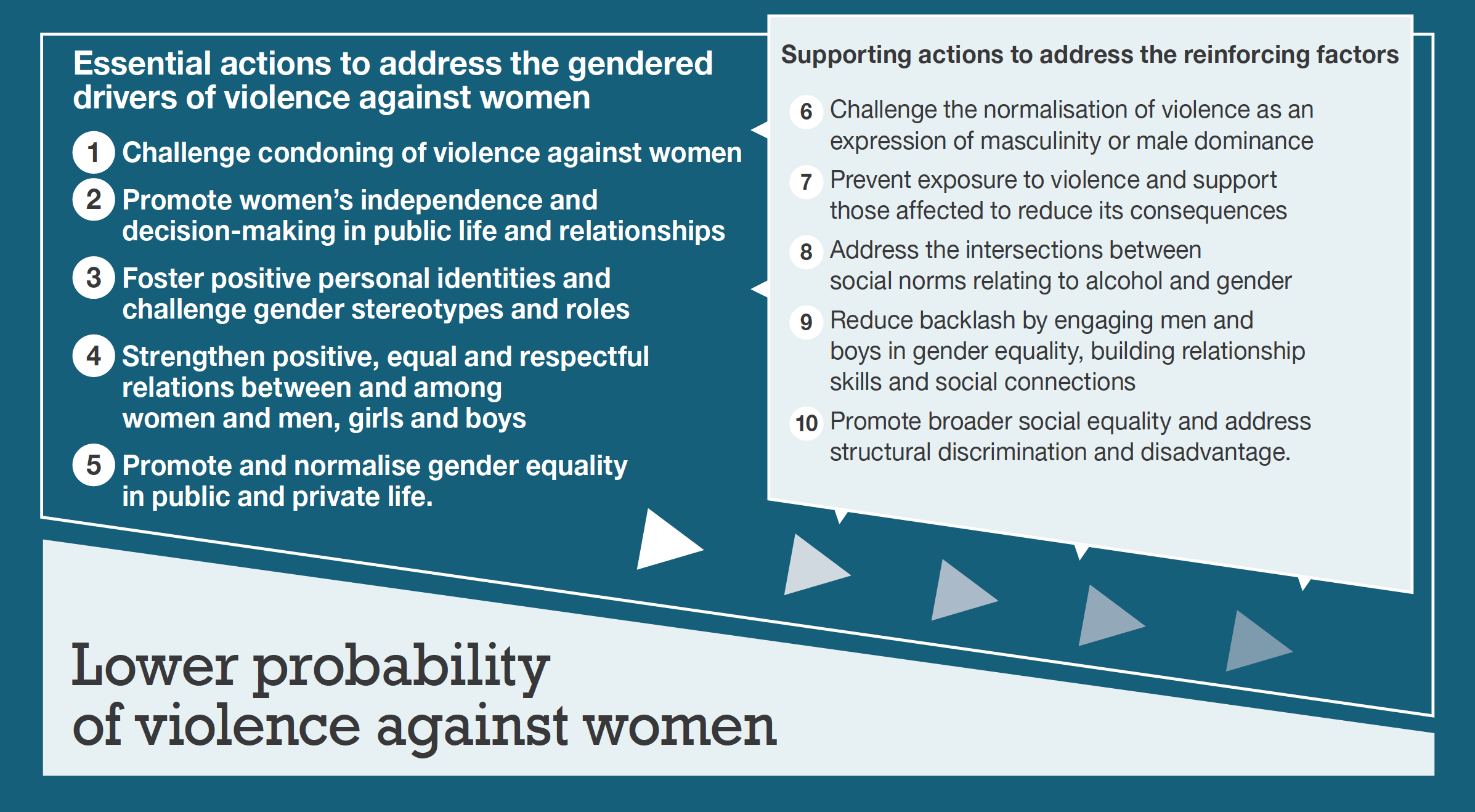

What we need to do

We endorse the following key actions from the Change the Story framework to prevent violence against women, and will work in our community to address these key platforms and actions. These key actions will help inform future social change, community education and engagement projects that are developed and delivered by the Centre for Non-Violence.

They are to:

• challenge condoning of violence against women

• promote women’s independence and decision-making in public life and relationships

• foster positive personal identities and challenge gender stereotypes and roles

• strengthen positive, equal and respectful relations between and among women and men, girls and boys

• promote and normalise gender equality in public and private life.